Romeo Oriogun’s The Gathering of Bastards is a profound exploration of displacement and socio-political consciousness, reflecting on the experiences of exile, migration, and the longing for home.

Through this collection, Oriogun explores the psychological and emotional toll of being uprooted from one’s homeland, while offering a creatively critical lens on the socio-political conditions in Nigeria that have prompted such mass departures.

In the review below, the critic takes a closer look at how Oriogun’s poems weave together varied reflections on identity, history, and spirituality, using powerful imagery of water, rivers, and migration to evoke the complexities of cultural dislocation.

Below is the brilliant review by Paul Liam.

Displacement is central to diasporic poetic aesthetics for the obvious reason that exile fosters a sense of cultural and political awakening that keeps the exile in a constant state of questioning his belongingness to a new space or place. The question of place and belonging has received renewed textualization by the new generation of Nigerian diasporic writers, especially, poets as they struggle to adjust to the new realities of their adopted countries. Also, exile inspires a deep and reflective self-evaluation that leads to the development of new consciousness and sentiment for one’s former country. This newfound consciousness manifests either in lamentation about the poor state of development of the homeland or in the expression of exaggerated admiration of the homeland, particularly through the celebration of their Africanness, cultures, and belief systems to cope with the sense of alienation caused by displacement. Romeo Oriogun in his work The Gathering of Bastards conceptualizes the idea of exile and displacement via the metaphor of a wanderer who has been removed from his habitat and now roams the world in search of permanence. But more than just the representation of displacement, the collection also undertakes a performance of socio-political commentary on the dearth of social justice and the impoverishment of the homeland which is also partly responsible for the mass exodus.

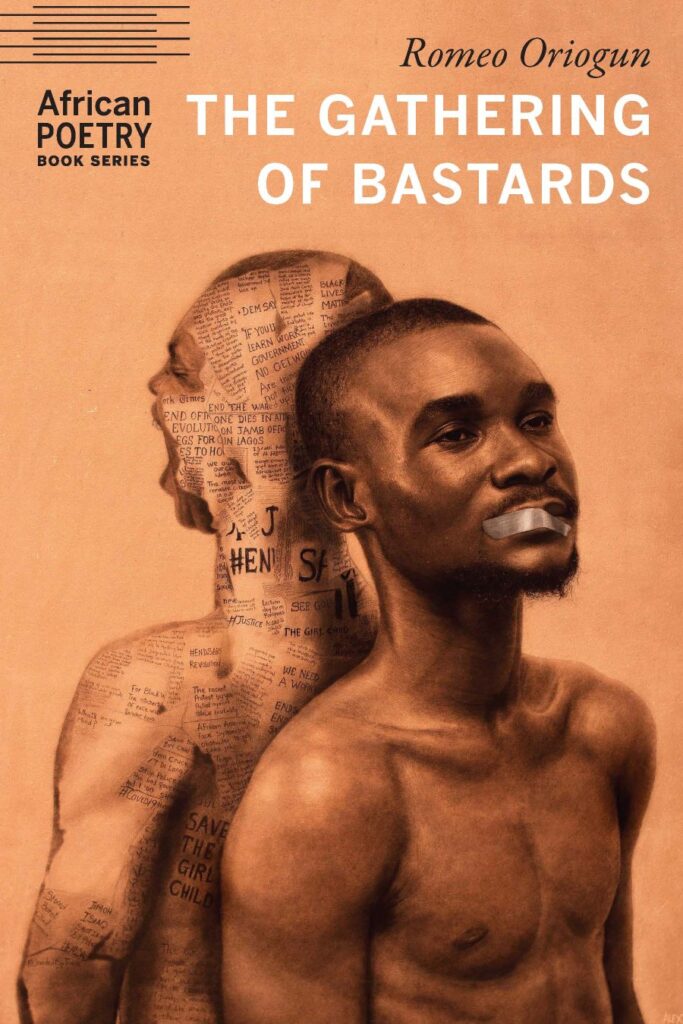

The Gathering of Bastards (2023) was published by the University of Nebraska Press under the African Poetry Book Series. Like Nomad (2022), The Gathering of Bastards x-rays the conundrum of exile, migration, displacement, angst against the homeland, and nostalgia. It offers an experiential reflection on the crisis of displacement occasioned by the hostile socio-economic system of Nigeria which forces its sons and daughters to become displaced in the vastness of the world. The collection also explores the tropes of displacement and socio-political consciousness resulting from the acquisition of a new consciousness enabled by exile. In other words, it is a reflection on the state of the homeland in the context of one who has been forced to become a wanderer by circumstances beyond his control. The underpinning discernible ideological trope in the collection is the supposition that displacement inflicts psychological and emotional trauma on the victims of forced displacement.

The images of the sea, river, and water hold both physical and spiritual importance in the collection. Primarily, the sea, river, or water functions as a route to a destination, and during the colonial era, the European imperialists came to Africa through the sea, rivers, and water using ships or boats and it was through the same means that they exported slaves and mineral resources out of Africa. The second import is that the sea, river, or water serve as a source of spirituality for many African societies. It also serves as a place of spiritual cleansing for Oriogun and reconnection to his spiritual essence. The concept of water and rivers as symbols of spirituality in African poetry has been linked to the important role of rivers as the source of life and death in African cosmologies. Okigbo’s homage to “Mother Idoto” the water goddess in “Heavensgate” and Okara’s tribute to the “River Nun” in “The Call of the River Nun” are illustrative of this assertion.

Oriogun is a fine poet whose literary exploration has had a significant impact on contemporary Nigerian poets, especially of the Gen Z era. An ardent follower of Oriogun’s poetic evolution and exile has to be familiar with his leading efforts in mainstreaming confessionalism and queer poetry in Nigeria even against the vicious cycle of repressive anti-homosexuality advocacies. His famous queer collection, Sacrament of Bodies (2020) serves as a reference point in the concretization of queer poetics in Nigeria. Little wonder that he remains a source of inspiration for emerging literary voices who consider him to be their role model.

Although it would seem that Oriogun has redefined his artistic thrust or found new poetic inspirations that are different from what he used to be known for. For example, Nomad is regarded as a refreshing break from the stereotypical Nigerian poetry that is often characterized by “monotonous social consciousness.” As already highlighted, The Gathering of Bastards is a departure from the tropes of confessionalism and queer aesthetics. As a poet grows in age and experience so also his priorities change along with the new experiences. This perhaps explains why we have seen a critical shift in the focus of his poetry since his dislocation and relocation abroad. It is this reasoning that has influenced the exploration of the subject of displacement and socio-political motifs in The Gathering of Bastards.

As already established, Oriogun transitioned from the personal and confessional to the communal or socially conscious aesthetics that speak to the collective travails of his humanity. This is an indication of a poet who has come of age and is no longer encumbered by the existential threats that once occupied his consciousness. By deconstructing the social-political realities of his homeland, he aligns himself with the notion that although poetry may be considered a personal endeavour it also enables access to the discourse of society helping to foster deepened enlightenment and awareness. The critic and scholar, Emmanuel Sule Egya in a public presentation commemorating World Poetry Day on March 21, 2023, entitled “Poetry as an Act” postulated on the significance of poetry to society thus:

…any time the poem on paper is read, its agency comes alive. The notion of a poem as an act collapses a poem’s private character and public character so that we dispel the thought of a private poem being distinct from a public poem. In my view, there is no such thing as a private poem (often said to be a poem dealing with private issues) as against a public poem (a poem dealing with public issues). A poem, instead, is a private-public act with a capacity to embrace all aspects of life. In other words, a poem is all-embracing, protean, and kaleidoscopic; its flux and flexibility are such that it defies definition, categorization, and boundary. This is the poem we should think of when we talk of national consciousness.

It is deducible from Egya’s submission that a poem functions in the service of the public even when it is conceived as a private or personal experience. This assertion is accentuated by the fact that a poet is a part of the larger society and his supposed private experiences or reality are rooted in the shared communal experiences of the society to which he belongs. A musician, for example, may sing of betrayal by someone he loved and while it is true that the singer’s experience is personal to him, the denotative implication of his song is that human beings regardless of their realities experience betrayal or know what it means to be betrayed. Similarly, Oriogun’s contextualisation of his encounters in The Gathering of Bastards speaks to the shared experiences, histories, and realities of Nigerians.

For example, in the poem “Ouida” (p.17), the persona speaks about colonialism, slavery, and what it means to live in a post-colonial society wrecked by European imperialism. Oriogun x-rays the loss of identity suffered by victims of colonialism which he symbolically represents with the bearing of foreign names by Africans.

He states in the second stanza of the poem:

The man said, the task is to understand

the land, not to claim it. There’s history

in the crash of waves, and in the water

we are reminded, every name we know

is written in a language that came through

the arrival of ships, through the betrayal of water.

In the last stanza of the poem, Oriogun alludes to the ‘Door of No Return’ which is a memorial arch in Ouida in the Benin Republic, which was a major slave port during the slavery era. Oriogun remembers the chains, whips, clangs, and blood which are reminiscent of the horrific experiences of the slaves who suffered dehumanization at the hands of white slave merchants. He opines that on the hottest of days, he runs into the coolness of water for respite but instead of enjoying the soothing calmness of water, it reminds him of the ‘violence of history’. In other words, for Oriogun, running into water is symbolic of the shipment of slaves across the sea.

In the poem “Crossing into Togo” (p.25), the persona engages in conversation with a journalist who appears to be a co-traveller with whom he shares the burden of exile and travails of their homeland. In the second stanza, the journalist declares, “Even the voices of our people/are dying in the river of democracy.” To which persona responds: “There are no more surprises in hearing/these stories—the madness of men weaving/havoc from statehouses has become a part of our diet.” Through their exchanges we feel their sadness and almost hopelessness with the state of affairs of their homeland; democracy has failed to entrench the development needed to better the lives of the people, and the failed leaders live in statehouses embezzling the country’s resources while the people wallow in poverty. The role of the West in the decay of the land is not lost on them as can be deduced from the following submission:

There, we are reminded of the cries of a people

singing that old song, which was the earth burying

her children, which was a fodder for a Western camera

throwing dead Black bodies across television screens,

in airport lounges, in offices across the Atlantic.

In the poem “A Stranger in Aba” (p.65), Oriogun pays tribute to the valor of the Aba Women’s Riot of 1929 against the oppressive regime of the colonial government. The Aba women’s resistance marked a significant milestone in the annals of Nigerian women’s struggle for recognition and inclusion in the larger society. The opening stanza of the poem provides an elucidating reflection on the struggle:

In the dying afternoon, the stereo was on,

the stockfish seller hummed to a song about the days

of women marching against colonial masters, sitting

on men, protesting with the nakedness of their bodies.

“The Last Days of General Abacha” (p.66-67) recounts the dehumanization of Nigerians by the suppressive regime of General Sani Abacha who was reputed as one of Nigeria’s most corrupt and brutal dictators. It was also during the military era that Nigeria began to experience its first wave of brain drain when some of its brightest brains began to migrate to Western countries to escape the harsh economic realities and indignity inflicted by the military government. While Nigeria has since become a democracy, the impacts of the years of militarization are still felt to this day and writers and intellectuals, especially continue to relive the gory memories of that unfortunate trajectory in Nigeria. Oriogun portrays what it meant to live in a dictatorship and the psychological trauma that many continue to live with today. Oriogun enthuses in the opening stanza thus:

As for those who are dead there is nothing

We can do other than imagine them living

Their lives under murky waters, in the canal

Of Apapa. There is nothing like victory

In a dictatorship; those who survive must carry

Within them the map of blood, the desire to find

Missing bones. Perhaps we all carry within us

The illumination of knowledge—though we had

No choice but to say, this is where they were shot.

Dictatorship like war leaves behind scarce that never heals. Bemoaning the trauma inflicted on the national psychic by the Abacha regime, Oriogun explains in the last three lines of the last stanza, how the hostile social economic climate led to the migration of many Nigerians to other countries, “I know there is no translation for our sorrow. /Still the boats will travel on them, ferrying those/who ran away from terror to where it all began.” These lines also indict the West for their role in enabling the dysfunction vested in Nigerians by the military dictators by suggesting that the common terror of the ordinary man now seeking refuge outside of their homelands is a result of the West’s interference in Africa.

In “Remembrance” (p.68-69) Oriogun narrates the horrific murder of innocent civilians in Asaba, during the Nigeria-Biafra civil war (1966-67). Oriogun remembers how those who were vocal in calling for the unification of Nigeria suffered the most havoc during the war. Oriogun also highlights the betrayal of friends who participated in the slaughter of their friends. The crux of the poem is encapsulated in the following lines:

The year running

back to 1967 when men clad in white were killed

like sacrificial doves while their mouths chanted

One Nigeria! Years after their death,

I watched a man look into my eyes

without regret as he recounted the moment

the land covered its ears as bullets reduced sons

to silence.

The poem “Waiting for Rain” (p.81) is a homage to the ancient kingdom of Benin and the men and women who died resisting European invaders. These legends have been immortalized via the statuses erected in their honour which adorn the popular Ring Road in the city of Benin to remind the people of their forebears who paid the supreme price for their freedom and dignity. The poem reads in part:

And the bats, those messengers, are always flying above

the statuses, saying to us in their wings,

blanketing the sky; saying; these bodies

now sculpted before you stood against the white men,

these bodies were the first to fall, then the walls,

then the city.

Oriogun posits that the invaders are certain to return perhaps to continue with their looting of the cultural artifacts and identity of the great kingdom. He states, “Today, I know they will come again, /bringing with them the old smell of gunpowder, /the smell of mud, the wind weeping its uselessness to history.” Memories are haunting reminders of grief nursed in silence, and through the consciousness of the persona, we encounter the unspoken angst in national discourses to avoid confronting the ugly past. But the poet is a prophet and speaker of truth which is found in the metaphors and images of a poem.

“In the Museum of Fine Art, I Remember Home” (p.94) is a remarkable poem that corroborates my argument that living in exile offers poets and writers a unique window of opportunity to retrospect on their relationship with their homelands which culminates in a newfound awareness that strengthens the connection to their roots. In the poem, the persona achieves unprecedented self-awareness while taking a walk on Huntington Avenue when he realizes that the museum and the city hold stolen memories of his history and humanity. Oriogun expounds on this assertion thus:

I have not disappeared from my history, I have not forgotten

the gnats that hovered over the lantern, the meat seller reciting

an old incantation. Today, I walked down Huntington Avenue,

the night of renewal approached me, the moon was becoming

a lamp to my past, shadows around me grew into the map

of a country. Everywhere I went held a stolen part of

my forebears; even the museum was filled with my disgrace.

For no reason, the crows came down from the birch tree

before me, starring into darkness. What evil has befallen

me has befallen those before me, throwing them out

of their countries. So, I prayed in the language of winds,

as sincere as a whisper going out on water, let me touch

my forehead on the doorpost of my home. And here,

tonight, in Boston, the air is alive with the souls

of dead exiles, the sky too, and the dodo bird

that sings in our faraway land is watching me, singing

the folktale of rivers waiting for the souls of lost boasts.

The profundity of portraying the awakening to a new consciousness shows poetic brilliance. His carefully selected words illustrate a dilemma of dislocation and exile. The poem speaks to the emptiness that locks us out of the historical truths that encourage the desire to leave one’s homeland for another. Sometimes, we need to leave home in other to find ourselves and true legends like Santiago in Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist (1988) testify to this. The poet’s postulation that “the night of renewal approached me” marked the critical point when he arrived at a new consciousness. He goes on to explain that this newness is made clearer by the ‘moon’ which became the lamp that enables him to see where he stands in the world.

In conclusion, The Gathering of Bastards is a metaphor for exilic consciousness and the spiritual balance that is sometimes missing in our lives and once we find it, we gain insight into the powers within us. For Romeo Oriogun, it took a walk down Huntington Avenue in Boston, United States of America to attain self-awareness and the gift of a powerful book to help us find our legend and consciousness.

Author’s Short Bio

Paul Liam is a notable Nigerian poet, author, and critic with several critical publications to his credit. He is the author of two poetry collections, Indefinite Cravings and Saint Sha’ade and Other Poems.

He is the founding co-editor of Ebedi Review and consulting art editor of the Daily Review Newspaper. He is also a strategic and development communication scholar currently serving as the Technical Assistant to the SA on Media and Communications Strategy to the Minister of Foreign Affairs.

The post “Displacement And Socio-Political Consciousness In Romeo Oriogun’s The Gathering Of Bastards” By Paul Liam appeared first on Channels Television.